The Book of Mormon, which the LDS Church today promotes as almost entirely spiritual in nature, was first seen by many as a treatise whose central theme was to incite Native Americans to violence against white settlers. Though seldom understood by modern members, it is one of the major reasons why Smith and his early followers were often seen by their neighbors as dangerous, even seditious.

Most modern members of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints imagine that Joseph Smith was only interested in building a spiritual following, but he was an empire builder with grand plans for himself at the head of a kingdom in the western frontier. It is fascinating to observe that, at its peak immediately before the Mormons fled, Nauvoo rivaled Chicago in size. Such scale helps to explain why politicians equally feared and courted the Mormon vote, as the tight-knit community tended to overwhelmingly vote for whomever their prophet endorsed.

To understand the full scope of Smith’s ambition and belief in the future power of the church he’d founded, it is important to explore the Council of Fifty, a hand selected group of his most loyal followers. The LDS Church today describes the obscure organization as a “… group chaired by Joseph Smith with the purpose of laying the foundation for a theocracy in preparation for the millennial reign of Jesus Christ.” [1]

The Council was integral in Smith’s larger plan to establish a “Kingdom of God” on the earth, with himself as the king who spoke to God and ruled unencumbered by a form of democracy he derided as “mob rule.” His perceived need to operate outside even the loose bounds of territorial authority prompted him to seek permission from the federal government to take control of large swathes of western territory to control for his own purposes. The goal of the secretive Council was nothing short of replacing the American Constitution. Historian Benjamin Park described this historical moment as “one of the most radical religious and political endeavors of the American nineteenth century.”

BLOSSOM AS THE ROSE

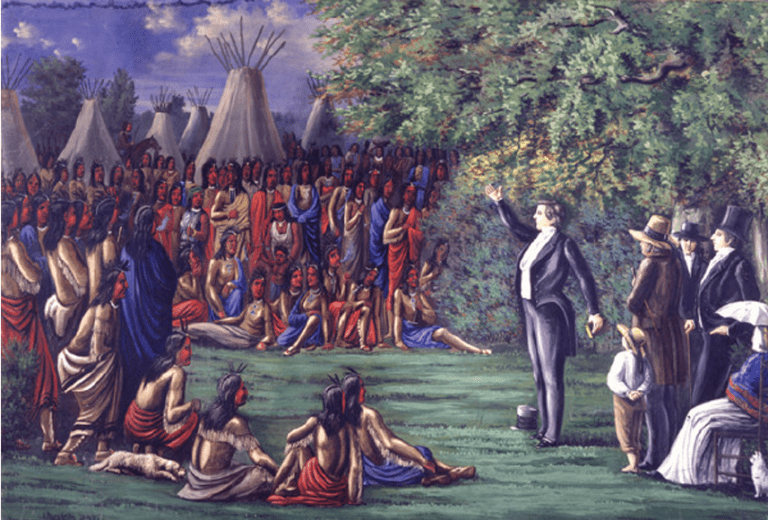

The narrative of the Book of Mormon suggests that the ancient Israelites who traveled here in a large sailing ship and became the ancestors of the American Indians were given both American continents as a “Promised Land” if they were righteous and obedient to the God of Christianity. Righteous Gentiles could of course gain adoption into the favored tribe, but the Lamanites alone were prophesied to “blossom as the rose” (D&C 49:24) after they embraced the restored gospel of Christ. Thus, Mormonism’s first proselytizing mission within Mormonism was directed toward Native Americans in June 1830. The Book of Mormon declares itself to be written for the descendants of the people it describes, and it is important for the largely white colonial descendants who make up the membership of the modern LDS Church to recognize the political power and danger inherent in the prophecies of the Book of Mormon.

In the later parts of the Book of Mormon, the Lamanite descendants (Native Americans) are told that God says, “…I will establish my church among them, and they shall come in unto the covenant and be numbered among this the remnant of Jacob [Native Americans], unto whom I have given this land [America] for their inheritance; And they shall assist my people…[to] build a city, which shall be called the New Jerusalem” (3 Nephi 21:22-23). Simply put, this is a call for native Americans to join the white/Gentile members of the LDS Church and to begin to build up an actual city, a political goal.

The rise of the literal ruling city named New Jerusalem was not an ambiguous threat to non-Mormons, as Joseph Smith clearly manifest its specific Missouri location in the name of the Lord. “Verily this is the word of the Lord that the city New Jerusalem shall be built by the gathering of the saints, beginning at this place, even the place of the temple, which temple shall be reared in this generation.” (D&C 84:1-4). Such biblical images were not merely spiritual in nature; they were a promise of God’s power standing behind the rising political influence of the early LDS Church and Joseph Smith personally.

Read closely and with the mindset of the frontier time period, it becomes clear that the role of the American Indian in LDS doctrine was not limited to mere spiritual redemption from their fallen state, but that they would unite and use force to reclaim God’s intended glory. So many white settlers on the frontier had already experienced violence as they moved from the eastern United States to the West, where Native Americans still controlled vast swathes of land. The Book of Mormon prophesies that the Indians would one day go forth “as a lion” to lay waste to their oppressors and reclaim the land of their inheritance. The Indians were to “go through among them [Gentiles], and shall tread them down, and they shall be as salt that hath lost its savor…to be trodden under foot of my people…” (3 Nephi 16: 14-16, see also 3 Nephi 21:12-21).

Though Indian sympathizers had been gaining prominence, Andrew Jackson’s election to the presidency of the United States in 1829 ushered in a dark era of Native American relations. President Jackson abruptly reversed policies of Native “civilization” and integration in favor of relocation, even extermination, which lead to the passage of the Indian Removal Act of May 26, 1830. As tensions rose, Mormonism was unique in promoting the subversive notion that God himself would soon raise up the Indians to destroy America.

Early Mormon doctrine did not go unnoticed and was perceived as a very real threat in American frontier towns where Indian relations remained tenuous. Missouri neighbors observed as early as 1833, “We are daily told [by the Mormons]… that we, (the Gentiles,) of this county are to be cut off, and our lands appropriated by them for inheritances. Whether this is to be accomplished by the hand of the destroying angel, the judgments of God, or the arm of power, they are not fully agreed among themselves.” [2] The intensity of concern only grew stronger as the Church spread, prompting Federal Indian agents to pen letters of concern, including an 1843 warning “that a grand conspiracy is about to be entered into between the Mormons and the Indians to destroy all white settlements on the Frontier.” [3] E.D. Howe similarly observed in 1834 that “one of the leading articles of faith is that the Indians of North America, in a very few years, will be converted to Mormonism, and through rivers of blood will again take possession of their ancient inheritance.”

Non-Mormon settlers on the frontier might have been rightly frightened and intimidated by the language in the Book of Mormon that purports to come from God: “I say unto you, that if the Gentiles do not repent…after they have scattered my people- Then shall ye, who are a remnant of the house of Jacob [Indians], go forth among them; and ye shall be in the midst of them who shall be many; and ye shall be among them as a lion among the beasts of the forest, and as a young lion among the flocks of sheep, who, if he goeth through both treadeth down and teareth in pieces, and none can deliver. Thy hand shall be lifted up upon thine adversaries, and all thine enemies shall be cut off…” (3 Nephi 20: 15-17).

Referring to any who opposed his plans as “adversaries” and “enemies”, Joseph Smith’s use of inflammatory rhetoric and images of lions tearing people in pieces was unlikely to ingratiate the neighbors who were trying to live peacefully around the new city of Nauvoo. He prophesied strongly, in the name of the Lord, of America’s pending destruction and rise of Zion. “I am prepared to say by the authority of Jesus Christ, that not many years shall pass away before the United States shall present such a scene of bloodshed as has not a parallel in the history of our nation. Pestilence hail famine and earthquake will sweep the wicked of this generation from off the face of this land to open and prepare the way for the return of the lost tribes of Israel from the north country. …Repent ye and embrace the everlasting covenant and flee to Zion [Missouri] before the overflowing scourge overtake you. For there are those now living upon the earth whose eyes shall not be closed in death until they see all these things which I have spoken fulfilled.” [4] While many modern members of the LDS Church have been taught that Smith was prophesying about the Civil War, his words were actually a threat of violence and insurrection supported by Mormon doctrines regarding Native Americans.

THE AMERICAN EXPERIMENT

In large part due to their belief that Mormonism was destined to assume a global theocratic leadership role in God’s grand restoration plan, early LDS leaders chafed under America’s budding democratic experiment, particularly where states’ rights led to tension in Illinois and Mormon expulsion from Missouri. Smith’s run for President of the United States in 1844 was part and parcel of his belief that only he could rule properly as God’s chosen servant. The LDS Church confirms Joseph’s desire to establish a new constitution to govern his theocratic government beyond the authority of the United States. [5]

Sidney Rigdon wrote in the Times and Seasons in 1844, just before Smith’s assassination, “A man is not an honorable man if he is not above the law, and above government… The law of God is far more righteous than the laws of the land; the laws of God are far above the laws of the land. The kingdom of God does not interfere with the laws of the land, but keeps itself by its own laws.” [6] Perhaps Rigdon had Polygamy in mind, but the implications and Smith’s actions extended far beyond that. Smith frequently operated without checks or balances because he was God’s mouthpiece to his followers, fleeing westward to remain on the edge of the American frontier.

The original purpose of the Council of Fifty was multi-faceted and far-reaching, including establishing a theocratic rule of government, supporting Smith’s run for the office of President of The United States, and exploring westward locations to secede from the U.S. Government. The Church’s newspapers, Times & Seasons and the Nauvoo Neighbor regularly promoted “General Joseph Smith’s bid for President of U.S.,” although Smith’s military credentials were self-appointed. [7] The organization was meant to be the municipal department of the Kingdom of God upon the Earth, from which all law would emanate. In some future state, Joseph envisioned himself as anointed as King to preside over the theocratic kingdom, second only to the King of Kings, Christ himself. In similar fashion as Mormon temple covenants, new members of the Council were required to swear allegiance and accept related penalties. [8]

This collective thought was the impetus behind the Council’s decision to send ambassadors to negotiate, in conflict with the United States, for territories in Texas and Oregon. Various regions of California and Canada were also studied as possible relocation sites. The ambitious Council sent Orson Hyde to Washington D.C. to solicit permission for the Church to raise a military force to oversee the Western Territories. Even before Smith’s death, it’s clear from The Council of Fifty minutes that Mormons were planning to move west because Nauvoo was not nearly large enough to contain their ambitions for power.

Lyman Wight summarized the Council’s adversarial attitude toward the U.S. Government when he proclaimed, “[The U.S. Government] is a damned wrotten [sic] thing…” Brigham Young went even further, prophesying, “I tell you in the name of the Lord when we go from here, we will exalt the standard of liberty and make our own laws. When we go from here we dont calculate to go under any goverment but the government of God. There are millions of the Lamanites who when they understand the law of God and the designs of the gospel are perfectly capable of using up these United States. They will walk through them and lay them waste from East to West. We mean to go to our brethren in the West & baptise them, and when we get them to give hear to our council the story is told.” [9]

Ultimately, Joseph Smith always placed himself at the head of any religious, political, civil or military organization, even when creating new offices and authorities as needed, and despite various positions having been expressly declared to be his equal in authority and power; that never was the case. Smith argued that he was a power unto himself, excusing anything he did against the laws of the land, or against common decency for that matter, as being sanctioned by God. He proclaimed himself to be a “committee of one” when instructing the “council to exert all their wisdom in this thing, and when they see that they cannot get a perfect law themselves, and I can, then, they will see from whence wisdom flows. I know I can get the voice of God on the subject… Let the Committee get all the droppings they can from the presence of God and bring it to me, and if it needs correction or enlargement I am ready to give it.”

Smith gave no quarter, even when referring to America’s Founding Fathers, a group so often heralded as divinely prepared and inspired of God in LDS discussion. He proclaimed, “There never has been a man in this age who could tell the people what the true principles of liberty was. [George] Washington did not do it. I don’t want to be ranked with that committee I am a committee of myself, and cannot mingle with any committee in such matters… When I get any thing from God I shall be alone. I understand the principles of liberty we want. I have had the instructions; it is necessary that this council should abide by their instructions. From henceforth let it be understood that I shall not associate with any committee.”

When Brigham Young moved west with the pioneers into territory that was not yet part of the United States, he also set himself up as the sole leader of an ambitious new theocracy, though it would not last long once the region became a territory of the United States. Young accelerated the inflammatory, separatist rhetoric soon after his arrival in the Salt Lake Valley, likely prompted by the renewed sense of protection the mountains and harsh climate afforded.

By 1857, there remained only one U.S. official in all of Utah, as the Mormons had driven out all others under threat of death. Anti-government rhetoric and violent doctrines, such as blood atonement, escalated nearly unchecked in Utah territory under Brigham Young’s leadership. Young declared in Sept 1857 the State of Deseret (Utah) to be a free and independent people, no longer bound by the laws of the U.S., while ordering Saints in California and Nevada to sell their property and return to Zion to fight the Government. The U.S. Congress declared Utah to be in state of insurrection and dispatched thousands of Federal troops to remove Brigham Young as Governor.

Upon reaching Utah, Young’s plans to baptize the Native Americans did not seem to be nearly as important as building a new kingdom with himself at the head; and if he saw the natives as equals, the sentiment was not reflected in any of his many interactions with them. Mormon settlers often engaged in violent conflicts (now properly called massacres) with the natives as they wrested land from them. Whether Young directly or indirectly encouraged such behavior, his rhetoric certainly sanctioned it.

BURN THE RECORDS

A final important point about the Council of Fifty is the way in which the historical record about this group was erased and the public image of Smith and Young as prophets, rather than earthly kingdom builders, massaged by later Church leaders into something more palatable. Only recently has the LDS Church been forced into a more honest admission of historical facts by the rise of the Internet and the easy distribution of material previously considered “anti-Mormon.”

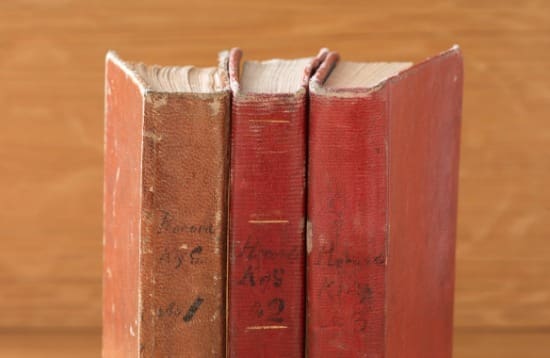

From the beginning, it’s clear that Smith understood how incendiary and possibly illegal the council was. Council rules instructed William Clayton, as scribe, to record and prepare minutes to be read at the next meeting, whereupon they would be burned. He often destroyed the minutes, but he and others frequently made notes in their personal diaries, based on the exciting discussions held in the meetings. These notes have helped piece together a more complete picture of the Council of Fifty today.

When Joseph was arrested in 1844 for destroying the opposition press in Nauvoo, he was also charged with treason for declaring martial law in Nauvoo. Understanding the damage the Council’s notes would cause, Joseph instructed his loyal scribe William Clayton “to burn the records of the kingdom, or put them in some safe hands and send them away or else bury them up.” Fortunately, Clayton preserved the records by burying them in his garden, soon thereafter transcribing the clandestine journals into three small books.

On February 27, 1846, Clayton crossed into Iowa Territory with the records in his possession. The records made it safely to Salt Lake City, where they remained closely guarded by the LDS Church. But in 1858, as the U.S. Army approached, the Council of Fifty records were again buried for several years to prohibit the incriminating philosophies from further exacerbating relations. The LDS Church continued to carefully guard the records for generations, restricting access for 172 years, first releasing the Council’s minutes in September 2016.

CHRONOLOGY OF KEY EVENTS

- February 15, 1844 – Members in Wisconsin Territory suggest the “table lands” in Texas as a possible gathering place.

- February 20, 1844 – Joseph Smith and the apostles at Nauvoo begin planning an expedition to Oregon territory and Mexican territories of California to secure a new settlement location.

- March 11, 1844 – Joseph Smith organizes Council of Fifty, in large part to secure settlement “in Texas or Oregon or somewhere in California.”

- March 14, 1844 – The Council sends Lucien Woodworth to Texas to negotiate Mormon settlement with Texas president Sam Houston.

- April 4, 1844 – The Council sends Orson Hyde to Washington D.C. to petition Congress to make Smith an Officer in U.S. Army with power to raise 100,000 troops to patrol western territories from Texas to Oregon.

- May 3-6, 1844 – The Council approves plans for Wisconsin Mormons to settle in the Republic of Texas.

- June 27, 1844 – Joseph Smith is killed.

- February 4, 1845 – The Council is reorganized, Brigham Young is appointed leader.

- February – March 1845 – The Council considers sites for settlement outside the United States, including territories in Texas, Oregon and California.

- March 11, 1845 – News of the annexation of Texas by the United States reaches Nauvoo, after which Mormons no longer consider Texas a viable gathering place.

- March 18, 1845 – The Council focuses its attention on California, near the Colorado River. Brigham Young said “it was Joseph’s mind that the head of California Bay was the place for us where we could have commercial advantages, but he also proposed other places for our consideration.”

- April 23, 1845 – LDS emissaries visit Indian tribes west of Missouri River to discuss obtaining refuge.

- August 1845 – Leaders receive positive reports about Salt Lake area.

- August 27 – 31, 1845 – Leaders meet to discuss exodus plans and potential locations.

- September 9, 1845 – Brigham Young announces his intention to settle “somewhere near the Great Salt Lake.”

- January 11-19, 1846 – The Council meets to finalize preparations to move west.

- February 4, 1846 – First group of Mormons crosses the Mississippi River into Iowa Territory.

- February 27, 1846 – William Clayton crosses into Iowa Territory with Council of Fifty records.

LEARN MORE

- The Joseph Smith Papers, Administrative Records: The Council of Fifty, Minutes 3/44 – 1/46.

- Wiki, Council of Fifty

- MormonThink, Council of Fifty

- Religion & Politics, The Mormon Council of Fifty

- Year of Polygamy, Episode 115, The Council of Fifty

- The Joseph Smith Papers, Legal Papers

- Worlds Without End, Council of Fifty Minutes, Brian Whitney.[1] The Joseph Smith Papers, Administrative Records, Council of Fifty, Minutes, 2016.

[2] Western Monitor, Fayette, Missouri, Aug 2, 1833

[3] Letters received by Office of Indian Affairs, Henry King to John Chambers, 1824-81.

[4] As printed in American Revivalist, also Rochester Observer, Joseph Smith, Jan 4, 1833.

[5] lds.org, Church History Topics, Council of Fifty.

[6] Times and Seasons, Sidney Rigdon, May 1, 1844.

[7] Times and Seasons, May 15, 1844.

[8] The Mormon Hierarchy, Quinn, 128-129.

[9] Council of Fifty Minutes, 1 March 1845.